Tendinopathy is a general term that describes tendon pain and a model has been presented that describes 3 stages of tendinopathy:

REACTIVE TENDINOPATHY, (a sort term adaptation to overload that thickens the tendon, resulting in pain and stiffness)

TENDON DISREPAIR (Can follow reactive tendinopathy if the tendon continues to be excessively loaded and the tendon can begin to change)

DEGENERATIVE TENDINOPATHY (More common in older athletes and is a response to chronic overloading)

Common sites include the rotator cuff (supraspinatus tendon), wrist extensors (lateral epicondyle) and pronators (medial epicondyle), patellar and quadriceps tendons, and Achilles’ tendon.

The exact aetiology is unclear. Studies suggest it is an over-use condition leading to inadequate tendon repair that predisposes the tendon to micro-tears and degeneration.

In athletes, common locations for tendinopathy include the Achilles’ and patellar tendons.

In the general population, the Achilles’ and lateral epicondyle are the most commonly affected

Current evidence suggests that management should include active rehabiltation. This mainly involves tendon loading and patient education. Tendinopathy rarely improves with rest or passive treatments alone because neither approach increases the tolerance of the tendon to load.

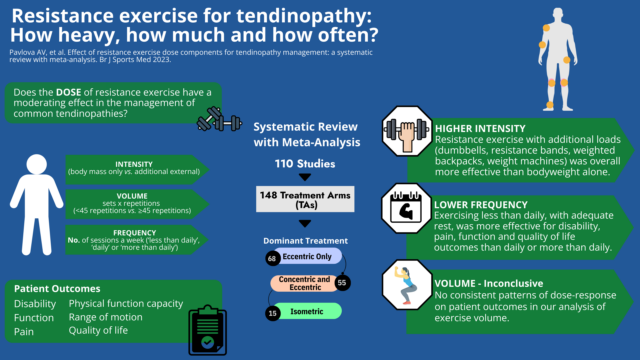

It was previously found that resistance exercise is most frequently prescribed (Cooper 2023), particularly eccentric exercise which loads the muscle during its lengthening phase. It is thought that by gradually encouraging tolerance to load, structural adaptations at the tendon and muscle tissue promotes recovery and restoration of function. As with any intervention, the effectiveness of resistance exercise is likely to be influenced by its dose, which can be described by the intensity, volume and frequency of exercise. While tendinopathy research has attempted to explore this dose-response relationship with resistance exercise, no clear recommendations have been made to date.

In a review (Pavlova et al BJSM 11 May 2023) 110 studies, with a total number of 3953 participants, that used resistance exercise therapy for treating tendinopathies were reviewed. They found that higher intensity resistance exercises which involved using external loads (dumbbells, resistance bands, weighted backpacks, weight machines) were consistently more effective at improving patient outcomes compared with resistance exercise that relied on bodyweight only. It appears that some studies prescribing resistance exercise interventions were not sufficiently loaded to bring about the structural adaptations required for tendon repair (Gatz 2020, Cho 2017).

Interventions where resistance exercise was done less frequently, with rest days, had better outcomes for disability, pain, function and quality of life than those doing resistance exercises daily or more than once a day. This is consistent with strength training principles which call for rest days to encourage better adaptive processes in the mechanical properties of tendons before further loading occurs. The most common number of total repetitions was 45 (e.g., 3 sets of 15 repetitions) but we did not find any consistent patterns of dose-response on patient outcomes in our analysis of exercise volume.

What are the key take-home points?

Clinicians prescribing resistance exercise should consider including higher intensities, that involve adding external weight, and should ensure adequate rest between sessions to facilitate recovery. Although some patients may need a longer period to build up their intensity it is important to keep reviewing whether the load intensity is adequate to trigger improvements.

TENDINOPATHY OFTEN RESPONDS QUITE SLOWLY SO IT IS IMPORTANT TO BE PATIENT AND STICK TO YOUR INDIVIDUALISED PROGRAM

If you would lie any advice on how to manage your tendinopathy and implement some strategies then please get in touch